Labor Day Blues: A Three Part Series on the Fight for a Fair Wage / Part One: Fight for $15 comes to Richmond, VA

By Melissa Ooten | RACE

By Melissa Ooten | RACE

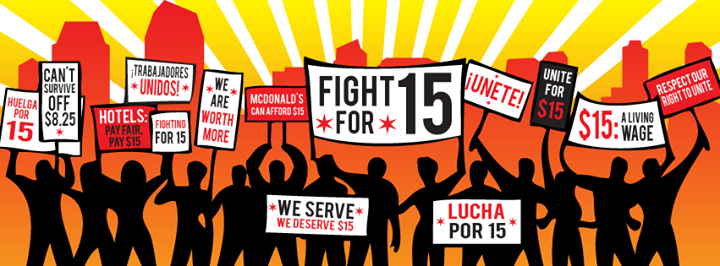

Part I: Fight for $15 comes to Richmond, VA

In mid-August, thousands of low wage workers traveled to Richmond, VA for the nation’s first Fight for $15 convention. The movement, begun in 2012 when a few hundred workers walked off the job at chain fast food restaurants in New York City, has gained momentum. And its effects have been substantial. As Time magazine reported last year, a number of cities will raise the minimum wage in the coming years. San Francisco will become the first in the nation to boast a $15 minimum wage when it goes into effect in 2018. Just two hours north of Richmond, lawmakers in Washington, DC approved a plan to reach a $15 minimum by 2020.

But this minimum wage will often only apply to certain workers. In New York City, the $15 minimum will apply solely to workers employed by fast food chains with at least thirty U.S. locations. In Seattle, businesses with fewer than 500 employees will have four more years to institute the $15 minimum than larger businesses do. But these discrepancies are no different than present minimum wage laws. While the federal minimum wage is $7.25, nearly 2 million workers fall into categories not covered by this minimum. From agricultural workers to tipped workers, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in 2014 that 2% of the nation’s workers were legally paid below $7.25 because the jobs they work remain “exempt.”

In the second part of my Fair Wage series, I’ll take up the continued problem with workers being exempt from an already paltry minimum wage. But for now, look closely at the examples listed above in terms of cities that have legislated $15 minimum wages. New York City, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, DC are always listed in the top ten most expensive cities in the U.S. They also represent some of the most expensive cities in the world in which to eat, live, and commute. These varying costs of living have long been cited as the reason why minimum wages should be based on local standards, not federal ones. That cost differential of housing, property, transportation, and food is perhaps at its greatest variance between the large coastal cities of the West and East coasts and the rural areas of interior states. Given these vast differences, and setting aside feasibility for the moment, is a $15 federal minimum wage necessary nationwide?

Let’s take Richmond, Virginia, where I live and the site of last month’s Fight for $15 convention. In 2013, Kiplinger.com named Richmond one of the nation’s most affordable cities to rent in the nation, noting its average rental cost of just under $900 per month. Earlier this year, Richmond made Realtor.com’s top ten list of most affordable, trendy cities, noting the city’s median home price of $170,000. So, at least by some measures, Richmond is fairly affordable.

According to MIT’s living wage calculator, a living wage for one adult supporting one child in Richmond would be $23.96 per hour, based on a full-time, year long work schedule. What does a living wage calculate? Based on local measures, it calculates the average local cost of a year’s worth of food, childcare (if applicable), healthcare, transportation, housing, taxes, and other miscellaneous items, like clothing, tampons, and toothpaste.

Let’s look at one expense alone. If someone secured an “average” rental in Richmond, it would cost roughly $11,000 each year. Yet a minimum wage employee, making $7.25 per hour working 40 hours per week for 52 weeks will make slightly over $15,000. Sure, there are some options for food stamps, housing vouchers, and other public assistance resources, but all of those options come with vast bureaucratic hurdles, an ever-evolving shortage of availability, an immense amount of stigma, and strict income qualifications. A minimum wage worker also wouldn’t qualify for much. By contrast, a $15 minimum wage would ensure that a worker who clocks 40 hours for 52 weeks would make slightly over $30,000 for the year. While that’s well below MIT’s standard for a living wage, it’s double what those workers currently make, and it would make their housing costs equal roughly one-third of their income, which has long been the nationally promoted standard in order for families to not risk their financial security.

But some might contend that Richmond is a still a city, albeit a smaller one with its population of roughly 215,000 residents. What, then, of rural areas? While housing costs often plummet, other costs rise exponentially. Public transportation is virtually non-existent; residents must rely on cars, and with low incomes, those cars are rarely reliable. And if a worker misses work and gets fired due to unreliable transportation, getting a job can be much harder given the lack of job opportunities, particularly ones within a manageable distance. Health expenses are often higher as well as people visit doctors less, given their relative isolation and the difficulty in accessing health services. While urban areas have 134 physicians per 100,000 residents, rural areas have less than 40 physicians per 100,000 residents. Rural residents, then, receive less preventive care and must travel much greater distances for emergencies, which then occur more frequently. Finally, rural areas remain more impoverished than the nation’s cities and suburbs, due to a decades-long exodus of young, skilled workers and negative job growth in general.

So where does that leave us? While a $15 minimum wage seems like a no-brainer for some of the nation’s largest, most expensive cities, it’s essential for workers across the nation as a whole, whether in “affordable” cities like Richmond or rural areas around the country. But there’s a nagging problem with this talk of minimum wages. Too many workers are still exempt from it, an issue I’ll address in part two of this series.

For Further Reading:

*Kathryn Edin and H. Luke Shaefer, $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America. New York: Meriner Books, 2015.

*Caroline Fredrickson, Under the Bus: How Working Women Are Being Run Over. New York: The New Press, 2016.

References:

-Steve Barkon, Social Problems: Continuity and Change. 2016. Available as on open online textbook.

-CNBC, “Some Exempt from Minimum Wage, Others Not,” 2014 April 16.

-Aaron Davis, “DC Gives Final Approval to $15 Minimum Wage,” 2016 June 21.

-Kathleen Elkins, “The 11 Most Expensive Cities in America,” Business Insider, 2016 March 12.

-Carol Hazard, “Richmond Makes List of Most Affordable Cities for Renters,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 2013 September 18.

-Victor Luckerson, “Here’s Every City in America Getting a $15 Minimum Wage,” Time, 2015 July 23.

-Yuqing Pan, “The 10 Trendiest U.S. Cities that You can Still Afford to Buy In,” Realtor.com, 2016 March 7.