A three part series on the meaning of the confederate flag from a semi-conscious white ally born and raised in the ex-confederate south.

Pt. I: Childhood, Image Based Knowledge, and My Media-Shaped History

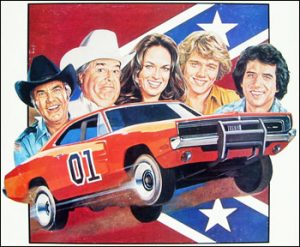

Childhood, a time of innocence, learning, socialization, growth, and awakening is also a time of great distraction. As a young child growing up in the mountains of southwest Virginia during the eighties, Friday nights in my family were set aside as a time to gather around the television to watch the Dukes of Hazard and the Incredible Hulk. We ate popcorn, drank pop, and made an evening out of it. Generally my parents couldn’t afford to take us out to the movies, except on Mondays when it only cost a dollar per person, and we would bring our treats from home in my mother’s giant handbag. These Fridays were paradise in this working class small mountain town on the fringes of the middle class.

The symbol of the “Good Ole Boy” is a common and persistent archetype in popular culture, particularly southern contemporary pop culture. As a young southerner, I was taken in by masculine images related to the flag of the confederacy for much of my childhood and misappropriating certain aspects of these was too easy. Instead of symbolizing oppression, white supremacy, and repression of people of color, they symbolized authentic rebellion, patriotism, and southern heritage to me. As a child who did not yet know what the civil war, or slavery, or oppression was, I knew what the General Lee was. I didn’t know who it was named after, and later, if challenged, I would defend the confederate flag as a symbol of southern working class pride. I was wrong.

Being an impressionable young southern white kid, I saw on that screen examples of strong, family oriented, young men on a hero’s journey reinforcing the spectacle of story and what it means to fight injustice. With Boss Hog’s riches and the local law enforcement under his control, I saw what I perceived as youthful authentic rebellion in the face of tyranny: just “good ole boys” fighting for what was right in a muscle car with the symbol of southern heritage and tradition drawn on its roof amidst high flying stunts and laser fast back road car chases. I was hooked. This is what I associated with the flag atop the car that good ole southern boys slid across and set aloft escaping from farcically crooked cops in the pockets of infinitely greedy bosses. This was what I wanted to be. Looking back, it’s stunning to contemplate how images can be manipulated in ways that shape thinking, beliefs, and values. Only later would I realize that this reshaping also molded my perceptions of history and social life while holding critical implications for my present day relationship to the southern collective institutional memory.

This perpetuated fabled southern mythology is what lies at the core of the current debate around the confederate flag. The pervasive branding of culture brilliantly blends images and ideology to reconstruct them into cultural identities in order to sell them on the marketplace in a repackaged history of selective remembrance. Guy Debord, in “Society of the Spectacle”, warns of the commodification of our image-based corporate media complex. Noam Chomsky highlights that a few media conglomerates control most of the information we read, watch, and consume in the corporate media, and how such commodification has guided our historic lens through a manufactured consent of a body politic that undermines our democracy. In Neil Postman’s seminal work, “Amusing Ourselves to Death”, he frames media images of the late twentieth century as an epistemology where knowledge is now based in the image. He thoroughly documents our society’s shift from a word based society to an image based one, and its often unexamined consequences. Robert Putnam, the sociologist who wrote Bowling Alone, discusses how the advent of the television reshaped communities, the family, and even neighborhood planning. He traces how families physically reconfigured their living spaces from those focused on familial relationship based communicative connections to those centered on the televised, image based media with an audience as subject. The television became both an altar and a gateway to the world outside the family walls. Our corporate media complex now has a captive audience with multiple screens not only in our homes, but also in our pockets. Many of these images intentionally shape our identities, our perceptions of history, and our cultural meaning systems. As a result, they fundamentally shape how we view ourselves, the world, and our social reality.

Being so tied to the image, it’s difficult to distinguish truth from fiction. Baudrillard aptly coined the term hyper reality when examining how the image and media reconstructs reality, simulates it, and presents it back to us, the “audience”, as a product. We begin to associate images of distant places and far lands with images created by Disney on sound stages and artificial theme parks. In his seminal text “Simulacra and Simulation,” Baudrillard contended that these images become more real than the reality itself. What does this mean in relation to how we understand meanings of the confederate flag?

When faced with accurate historic evidence, many of us might cringe with defensiveness at what threatens our world view. I contend that in order for us to eradicate racism, white people, particularly those raised in the south, need to run headlong toward what challenges us to dismantle our white supremacist mis-education. Social, economic, and racial justice cannot be actualized in a society where those with privilege do not experience paralyzing discomfort. What I will cover in the next part of this series may cause some of my favorite people to cringe, shake their heads in disbelief, or deny the power of the confederate flag as a symbol of oppression. I urge them to keep an open mind, and critically examine what is truly at the root of the meanings of the confederate flag as a symbol, because what it meant to the confederate congress is explicitly written into its history.

Pt. II of this series will specifically highlight the work of William Tappan Thompson and the role of the confederate congress in creating the confederate flag.

References

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation (The body, in theory: History of cultural materialism). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Debord, G. (1967). Society of the spectacle. NY: Zone Books.

Herman, E., & Chomsky, N. (2002). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. NY: Pantheon.

Postman, N. (1985). Amusing ourselves to death: Public discourse in the age of show business. NY: Penguin Books.

Putnam, R. (2001). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of the American community. NY: Simon & Schuster.