In my last piece, I discussed the two million jobs exempted from the federal minimum wage laws. I also noted the Obama administration’s plan to significantly increase the number of workers eligible for overtime. That plan is now delayed and may never be implemented. Meant to take effect earlier this month on December 1, a federal judge issued a preliminary injunction to stop the rule from taking effect back in November. Implementation is now indefinitely postponed, and the new presidential administration is unlikely to support that implementation regardless of the judge’s eventual ruling.

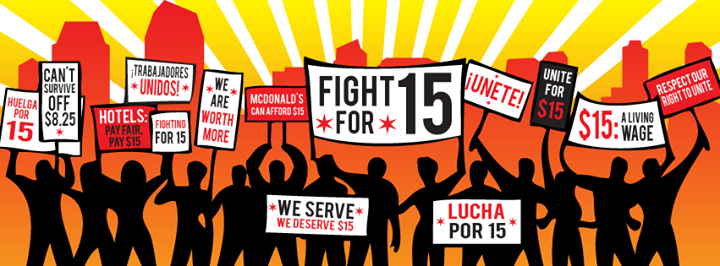

Current movements for increased minimum and living wages link to broader social justice movements like #BlackLivesMatter. When 10,000 low-wage workers came to Richmond, Virginia this past summer for the first ever Fight for $15 convention to demand a livable minimum wage of $15 per hour, they chose Richmond strategically due its former status as the capitol of the confederacy. According to their national organizing director Kendall Fells, the group deliberately wanted to link the racist history of the U.S. with present-day fights for better treatment of low-wage workers, who are most likely to be people of color.

At the conclusion of the Richmond convention, thousands of participants marched from Monroe Park to the Lee Statue on Monument Avenue. Both locations are deeply symbolic. Monroe Park, which is currently closed for renovations, is known as an area where dozens of homeless individuals gather daily. While the park is rigorously policed after dark to ensure that those without homes don’t sleep there, it often served as a daytime congregating space for those with unstable or no housing. And whether those folks will be welcomed when it reopens is a hotly contested question given the park’s prominent position alongside Virginia Commonwealth University’s campus and downtown Richmond.

While the march began at Monroe Park, it ended at one of Richmond’s most visually dominant monuments, a sixty foot statue of confederate general Robert E. Lee astride his horse, Traveler. The city built the Lee monument in 1890 to spur growth westward from the city’s center. At the time, it sat in the middle of a tobacco field during planting season. But the statue also sought to shore up nostalgia for the “Lost Cause” at a time that coincided with a resurgence of white supremacy as states throughout the South began legally enshrining white supremacy through discriminatory laws that separated the races and all but eliminated Black voting through Jim Crow laws. When Virginia’s legislators met to draft a new state constitution in 1901-1902, they crafted a document that disfranchised most Black voters as well as many white voters who did not own property. While Black Virginians accounted for more than one-third of the state’s citizenry at the time, they would not regain the right to vote until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In the years following the Constitution’s adoption, the Lee Monument became one of several statues dedicated to the confederacy along what would become known as Monument Avenue. The president of the confederacy, Jefferson Davis, confederate general Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and others lined the avenue by the 1920s, while the state continued to legally codify white supremacy. For example, in 1924, Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act, declaring that if someone had as much as “one drop” of non-white blood, that person would be legally considered “colored,” to the use the historical term of the time, and relegated to second class citizenship.

The fact that the Fight for $15 activists marched down Monument Avenue is not only deeply symbolic but also visually disruptive. A group made up overwhelmingly of people of color peacefully claimed space so long designed, both in reality through segregation and visually through monuments that glorify the confederacy and its attempt to preserve slavery, to promote white supremacy. Fight for $15 activists know that their fight is not caught up only in low wages but in who earns those low wages and why.

On November 29, thousands of fast food workers, baggage handlers, homecare workers and many other low wage workers marched and went on strike in hundreds of cities across the country. Undeterred by the recent elections that organizers said made organizing more important than ever, workers marked the fourth anniversary of the movement with more demands while also publicizing the gains they have already made. (Several cities, from Washington, DC to Seattle, will indeed soon raise some workers’ wages to a $15 per hour minimum).

But they weren’t just demanding a fair wage. They also marched against employer retaliation for their efforts, against deportation, against police killings of people of color, and in support of Obamacare, a health plan that has provided many workers with the care their employers refuse to offer. This movement represents the best of coalition building. There is no single platform for low wage workers because one small bump in the road, from an illness to a late day at work because a childcare plan fell through, is the difference between making it or not. Because more than half of African American workers and nearly 60% of Latinx workers earn less than $15 an hour, the Fight for $15 centers racial justice. A fair wage means little if the institutionalized racism that kills, deports, and otherwise perpetrates violence disproportionality upon people of color doesn’t end. It’s a movement we should all get behind.

One final note: I want to underscore how dangerous this type of work always has been and remains today. On December 7, the president-elect tweeted that Chuck Jones, president of United Steelworkers, had done “a terrible job representing workers.” My hunch is that Jones did his job in trying to support workers rather than the multi-billion dollar ($12.5 billion, to be exact) Carrier corporation for which they work. And due to this work, the president-elect called him out by name via a smearing comment in the most public of venues: Twitter. As the Washington Post reported, Jones immediately began receiving threatening phone calls. Jones is white, and some of the workers he represents make over $15. But the time for a multifaceted, diverse contemporary labor movement led by the nation’s most vulnerable workers, low-wage earning workers of color, is long overdue. That time is now.

References:

Jeanne Sahadi, “Millions may now lose eligibility for overtime after ruling,” CNN Money, November 23, 2016.

Jake Burns, “Why ‘Fight for $15’ Movement Picked Richmond for Convention,” WTVR.com, August 11, 2016.

Clint Rainey, “Fast Food Workers will Strike for $15 Wages in Hundreds of Cities Today,” Grub Street, November 29, 2016.

Reina Gattuso, “Fight for $15 Workers Plan Massive Strike for Labor Rights, Against Racism,” Feministing.com,

Danielle Paquette, “Donald Trump Insulted a Union Leader on Twitter. Then the Phone Started to Ring,” Washington Post, December 7, 2016.

Irene Tung, et al, “The Growing Movement for $15,” National Employment Law Project.

Encyclopedia Virginia, The Racial Integrity Act.