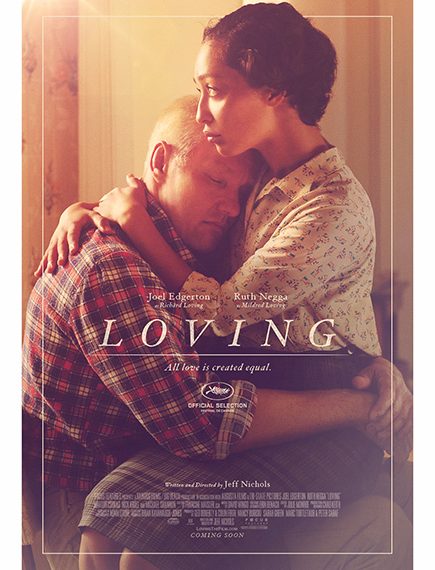

As Oscar season approaches, several films that address past and present issues of race and sexuality will vie for nods from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Here, I want to explore one of my favorite of these films this year: Loving.

Loving explores the relationship between a white man, Richard Loving, and a black woman, Mildred Jeter, who married in Washington, DC during the summer of 1958 because the state of Virginia in which they resided forbade interracial marriages. Eventually, the Loving case wound its way to the United States Supreme Court and in 1967, the highest court in the land struck down miscegenation laws in its ruling in Loving v. Virginia. This film explores the quiet, resilient way in which the Lovings lived their lives as they pursued their legal right to marriage in their home state.

It’s no coincidence that the Supreme Court case involving interracial marriage (dubbed “miscegenation” during the Civil War to denote racial mixing in the most derogatory of senses) concerned the state of Virginia. The first permanent English settlement in what would become the United States of America established roots in early seventeenth century Jamestown. Twelve years later, in 1619, the first slave ship arrived in North America. The shipmasters traded those Africans, who were enslaved people from Angola, for supplies.

Before the end of the century, in 1691, the colony of Virginia became the first North American English colony to ban marriage between free blacks and whites. While laws previously existed to regulate and restrict certain marriages based on one’s condition of servitude, this law became the first to do so by race.

Virginia also took the lead in attempting to categorize who could claim which race. In 1924, the state passed the Racial Integrity Act, which attempted to enshrine the “one drop” rule. This law attempted to establish that people who had as much as “one drop” of non-white blood could not claim the privileged status of white in the state. (Remember this is at the height of segregation and nearly complete voting suppression of African Americans in the state). The Act required that one’s race be recorded at birth, with the only two options being “white” or “colored.” It also criminalized all marriages between those classified as white and those classified as colored. Among other problems this law created, it meant that many native people in Virginia would have their ethnic identity permanently altered on public documents, making it nearly impossible for Virginia-based tribal communities to meet the standards for federal recognition in the future. Thus Virginia’s division of people by socially constructed racial classifications continued for centuries as the state increasingly tried to limit who had access to the privileged status of whiteness as the twentieth-century waned onward – at a time, of course, when movements for civil rights increased exponentially.

Loving fits into this story in its own unique way. It tells the story of a couple who, in many ways, wanted the freedom to live their lives in the communities in which they grew up with as little fanfare as possible. After all, rural Virginia in the 1950s and 1960s was certainly not a welcoming community for an interracial couple at a time when “race traitor” was likely the worst insult someone could lob at a white person and when white supremacists across the South intimidated, attacked, and even killed African Americans for trying to secure basic civil rights, like voting and a decent public education. You can see this play out in the film in that the couple lives in, and Richard spends his free time in, communities of color.

But the film isn’t a historical drag. It’s a deeply emotional exploration of two people trying to live with the person they love and raise their kids in a community with kin who share their values. At a time when the right to love who you want again seems more threatened, and threatening, and when much white anger undergirds politics, it’s a heartwarming tale that the U.S. indeed may be able to sometimes live up to its lofty ideals, even if that may seem far removed from much of our present.

For further reading:

Chief Justice Warren’s Opinion of the Court, Loving v. Virginia, 1967.

Warren Fiske, “The Black and White World of Walter Ashby Plecker,” Virginia Pilot, August 18, 2004.

Pippa Holloway, Sexuality, Politics, and Social Control in Virginia, 1920-1945.

Lisa Rein, “Mystery of Va.’s First Slaves is Unlocked 400 Years Later,” Washington Post, September 3, 2006.